Twenty Two

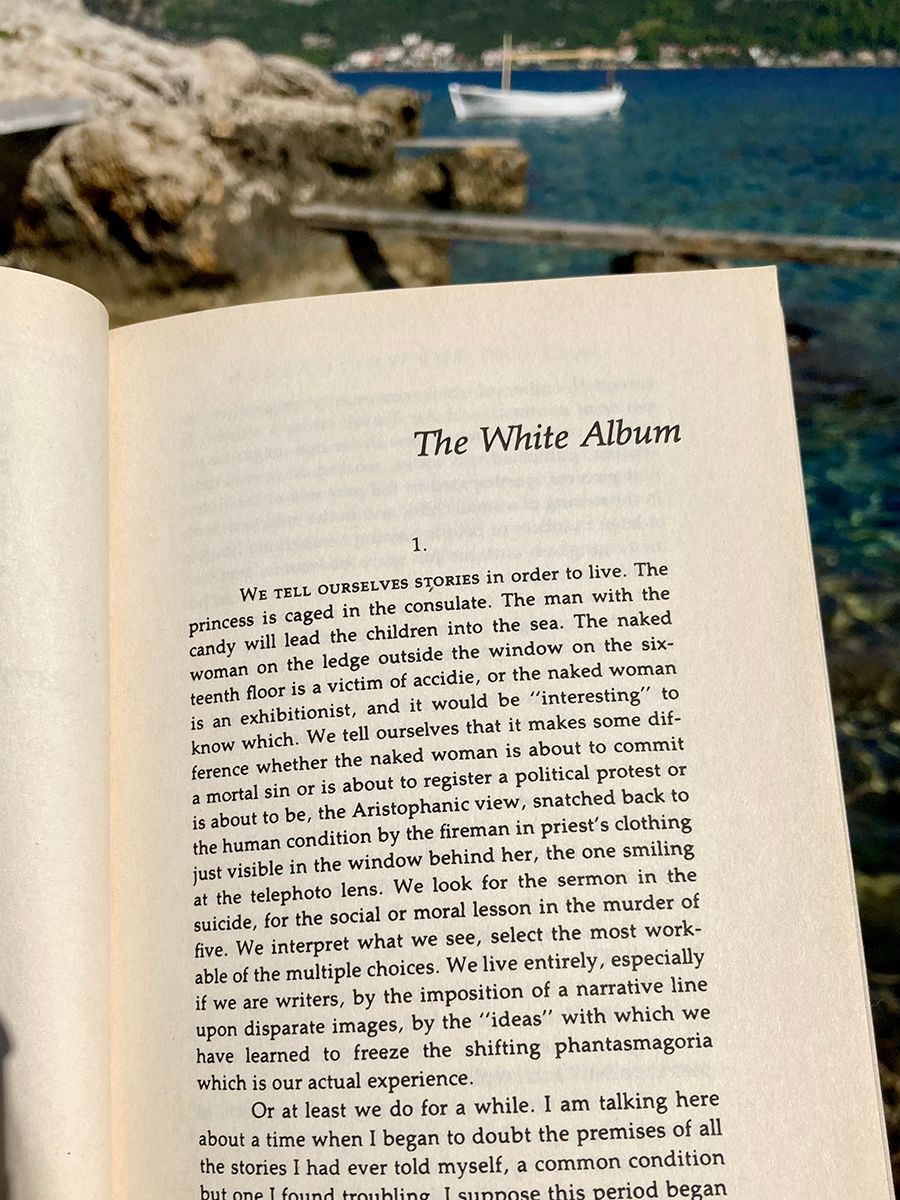

"We tell ourselves stories in order to live. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria, which is our actual experience." — Joan Didion, The White Album

It was her third time on the island. She had been there in 2022, 2023, then skipped a year, and returned now.

She always came here burnt-out, seeking solitude and quiet, unable to communicate with people or enjoy breathtaking nature—its beauty only amplified her overwhelmedness. A long-awaited vacation every time morphed into a tormenting retreat, where, in order to finally get a break, she was supposed to face her demons first. All she felt in the beginning was guilt, anxiety, irritation, alienation. Demobilisation, she called it. Living through the war is not what we are born prepared for—and when your psyche finally has a chance to relax, you merely turn into a wreck. Weird, but in previous years, it took her exactly 3 weeks to start breathing again, as if on the 22d day something in her chest loosened its grip.

This year, she came not even exhausted—likely in a continuous, silent nervous breakdown; those had been two extremely difficult years. On the island, at first sight, all remained the same—and this was, in a way, pacifying. The same tough-looking woman, Ivanka, with the same haircut at the same cash desk in the local supermarket, where fish was still delivered on Thursday mornings. The same navy-blue fisherman’s speed boat cruising between islands. The same striped cat living in a turquoise 2-floor cat mansion next to a wine shop, the same clone cat in the clone mansion next to the post office; another striped fatty living across a photo-lab, the same black, grey and red cats living on the steps of her street leading to the cathedral. Seriously, same cats two years later? So many people she knew were already dead. Even the same cloud was forming on the hilltops of the neighbouring peninsula.

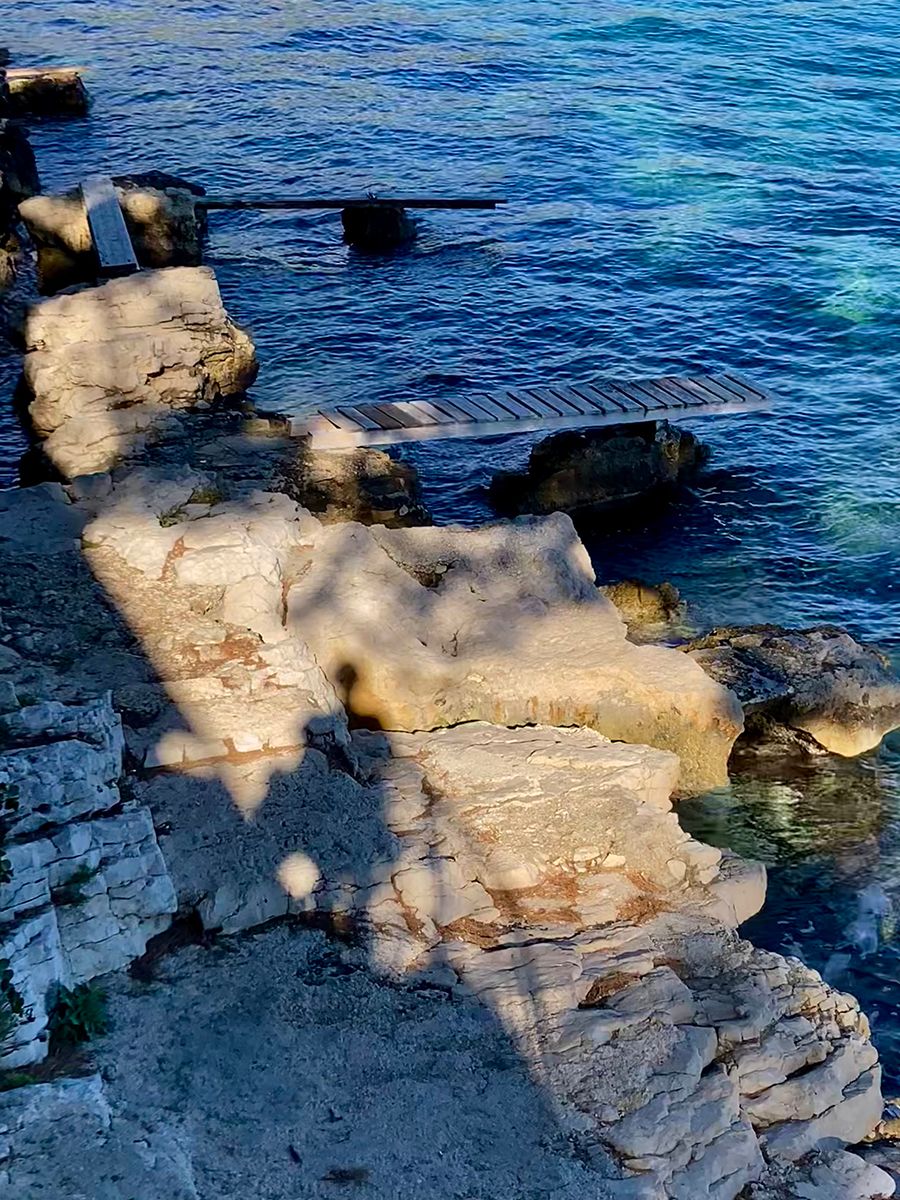

It was all the same, unless the sun was now going away from her beach significantly earlier than it was in her last October here. The pines must have grown crowns, she concluded. Not a bad thing. Also, garbage sorting stations next to the ports became card-paid. Okay. E-scooters became popular on the island. Convenient. The friend’s house she stayed in got nice old-style wooden window shades to prevent it from winter winds, and there was no more of that blinding light in the room in the morning. The immediate access to a piece of the ultramarine sea in the narrow cut of the alley was gone, too, though. Next to the western lighthouse, 21 young pines were planted, forming an alley to the beach. Good, but too clustered. And the wooden fishermen’s berth she would always lie sunbathing on was missing two planks now. The first time she came here, it was whole; the last time, there was one plank missing, which in a way made it even more photogenic—and now two. Hm.

There was a major change, though: the neighbouring elderly auntie Antica had died last year, and no one greets passersby anymore with repetitive ‘Jutro! Kuda idemo?’, sitting from dawn to dusk at the bench under the giant pine tree in a red knitted sweater. And nobody asks her “Plivati?” nor looks after her swimming in the October sea alone, waving her from the embankment. It was predictable, Antica was in her 80s, and yet.

However, she braced herself to survive the first 21 days, and then start enjoying life, and maybe even write another therapeutic short story to edit on her long way back, like in the last visit.

She responsibly went to the beach every day to sunbathe; she swam in the chilly sea, walked in the forest, ate fish, avoided people and did her best to restore. On the 8th day she seriously considered going home—to power blackouts, missiles, drones and daily deaths. The hell inside her, managed for so long, broke loose. She didn’t sleep a single night more than 2 hours in a row and spent half the night awake, trying to hop off the carousel of depressing thoughts, and listening to the sounds: of cathedral bells ringing every 15 min, of the sea that would start boiling at 5 am, in sync with the early little birds; of lark men hopping upon uneven wide street steps at 6; of wind whistling through the planks of window shades; of restaurants uploading stuff, of loud locals’ talks, of raindrops hitting both the tent of a veranda umbrella lying in the alley and her raw nerves. It was really storming in her head, so on the 9th day she just began working—it was better than her idle mind producing monsters.

Around the same time she came up with the idea to fix the pier. It was HER pier, she considered it hers, she had spent, in total, six terrible and terrific months at it, she called it her ‘charging station’, its photo was at her desktop and on her bedroom wall—and if you consider something yours, taking care of it might be the only appropriate way of appropriation, she thought. No pun intended. And may it be her small contribution to the local community. She didn’t want to come next year and find a hole at its place.

Also, she believed in the power of symbolic gestures—life leaves you scarred, damaged, ‘pre-loved’, they say; everything around is crumbling and disassembling—so maybe, maybe, if she manages to fix it, she will somehow confront, take over this continuing disruption, and fix herself too. Besides, it’s just inconvenient, she might drop the phone there, or stumble—she already dropped a book; the paper was so cool—it floated.

So she developed a plan. She just needed a few planks, a few screws, a saw, and a screwdriver. Or a hammer. A stone would do too. Preferably, no people involved. Nothing unrealistic.

Now she strolled through the old town with a strong sense of purpose—to find boards and the sound of an electric saw. She discovered a construction site nearby; men were cleaning something like an old chapel. She wasn’t in the mood to talk to anyone, so she just spent the next week patrolling the area with a measuring tape. Until one day she saw the wagon full of construction garbage, and there, among cement, were boards! She was examining them when a construction guy approached the wagon with another load, so she was forced to explain to him in a mix of languages that she needed these planks, very much. The kind man extracted from the pile of trash four boards she pointed to. It seemed like the first stage was done, but when she brought them to the beach and tried, the boards turned out to be too uneven in thickness and material—her pier needed to be fixed with all aesthetic requirements. So she continued her search.

And she continued waiting for the magical 22nd day of her vacation to feel better. It would fall on November 1st, the All Saints Day. What a fitting day for a tiny miracle, she thought. Could be autosuggestion, but on the 22nd day, for the first time here, she slept all night through. Yet the thing in her chest still hadn’t unclenched.

But on November 1st the tourist season was officially over, and street restaurants began disassembling their verandas to preserve them till the next season, and this was it—their wooden floors were made of the same deck board her pier was made of! Mostly dyed brown, but who cares—the sea will wash it off. So she began patrolling dismantling sites, until one morning she found a disassembled veranda floor, full of boards—and screws! She picked up a whole handful of screws and 4 planks of approximately needed size. Where there's a will, there's a way!

She checked them at the pier—they fitted like a glove, she just needed to cut them a bit; a house owner messaged that he had an electric screwdriver in storage—bingo. Now, the only thing she needed was a saw.

The next few days she listened to the sounds of town, hoping to hear the one that she, as everybody else, would normally hate; and put a phrase of her request into Google Translator to be ready. So, when one morning she was awakened by it, she rapidly walked outside with a cup of coffee. On a half-dismantled veranda a house away she detected 2 men. The deadline started to pressure, so she took a full chest of air—talking to strangers even before she had her first morning coffee—and approached them.

Two middle-aged men were sitting under a magnificent tobira tree that dropped small yellow goldfish-like leaves, enjoying their tiny Illy’s cups of espresso—pretty aesthetically, must say. One of them looked like a rock band frontman—a leather jacket, silver hair, trendy cut, a silver ring in the ear. An open toolbox was sitting at the edge of the empty veranda. She stared at it —there was no saw in sight.

“Bok. Excuse me, do you speak English?”, she then asked.

The rocker guy shook his head no and gave her a look saying rather, “What the fuck did you forget here?”

“A little”, another guy made an indefinite gesture.

“I just heard a saw, was it yours? If yes, can I borrow it? I need...”

The guys didn’t seem to get it.

“Ah, hold on, Google translator”, she handed out the phone with the translated message to the frontman who read it aloud in Croatian: “Sorry to intrude, do you by any chance have a saw? I need to cut off a few planks, I’m trying to fix the pier at our beach.” He passed the phone to his pal, nodded the way she read as approving, and said in English he suddenly learnt, “We had it, but they've taken it away already.”

“Any chance they will bring it back?”

“No. But you should ask locals around.”

“This is exactly what I’m doing”, she didn’t say. “Thanks!”

She visualized herself approaching every second man remaining in this town with the question, “Are you local? Do you have a saw?”, and decided to pick the least evil—to check the already known construction site at the chapel. You bet they have it. Right away, before she lost enthusiasm, she headed there with a bunch of already marked boards under her armpit, and a measuring tape. The middle-aged man, already familiar to her, and a young handsome guy in a black t-shirt with ‘ROME’ printed over his heart were standing at the entrance.

“Bok”, she handed Rome the phone with Google translator.

“No probs, I can do that easily”, he responded in Croatian, enthusiastically.

She showed him 60 cm marks made by a red pencil, “You see? To cut like that.”

“Wait here.”

He disappeared in the arch and got back in 8 min with all the work done.

“Sorry, these are too short, there was no space…”

“It’s okay! Bravo! Hvala lijepo!”

She ran home, found the electric screwdriver in the closet and, fully equipped, hugging it and a bunch of boards, stepped downstairs to the beach, ready to complete the mission.

“Are you going to fix something?”, turned the grey-haired old gentleman with whom for the past month they have been hanging at the same beach. He, she, a bartender, and a redhead woman were the last swimmers, at least on the Eastern shore. They’d never talked before, rarely greeted—she avoided people and respected their privacy.

“Yes, the pier. It is my third time here and every time I come, I see it deconstructed more and more.”

“Good, good!”

It was good indeed, except the electric screwdriver made a few weak rotations and stopped.

“May I ask you?”, she, on the contrary, was unstoppable today. The gentleman rushed towards her. “Not sure how that thing works. It doesn’t. Discharged?”

“Yeah. You need to take this block off, put it in charge and take another one. You have it?”

“Ah, thanks, I hope I do, at home. Or I could use just a stone instead.”

“No, it wouldn’t work.”

At home she changed the block and found a small, like a children’s, hammer. In a few minutes she was waving it in front of the gentleman at the beach.

“Nah, too light. You need something really heavy.”

“Wait.”

He didn’t know the weight of the things she carried within.

She climbed at the berth and started nailing the first plank. It wasn’t easy—she had to apply all her fury into this tiny hammer—but it worked perfectly. In 15 minutes, she not only covered the hole with two new planks, but secured all the old ones that were loose. She ensured that when she came the next year, her berth would be there in its entirety and beauty. Yes, now the two darker planks looked like a post-op scar on its white-washed wooden body, but in a year or so it won’t even be visible, the sea will fix it.

The first thing she did was take a photo of the repaired berth and go to the construction site. She met Rome halfway in the alley.

“Look, we did it”, she showed him the pic.

“Bravo!”

“It’s a Ukrainian-Croatian project”, she grabbed his hand and shook.

“It’s dirty!”, Rome got confused, but she didn’t care. She was really, really grateful.

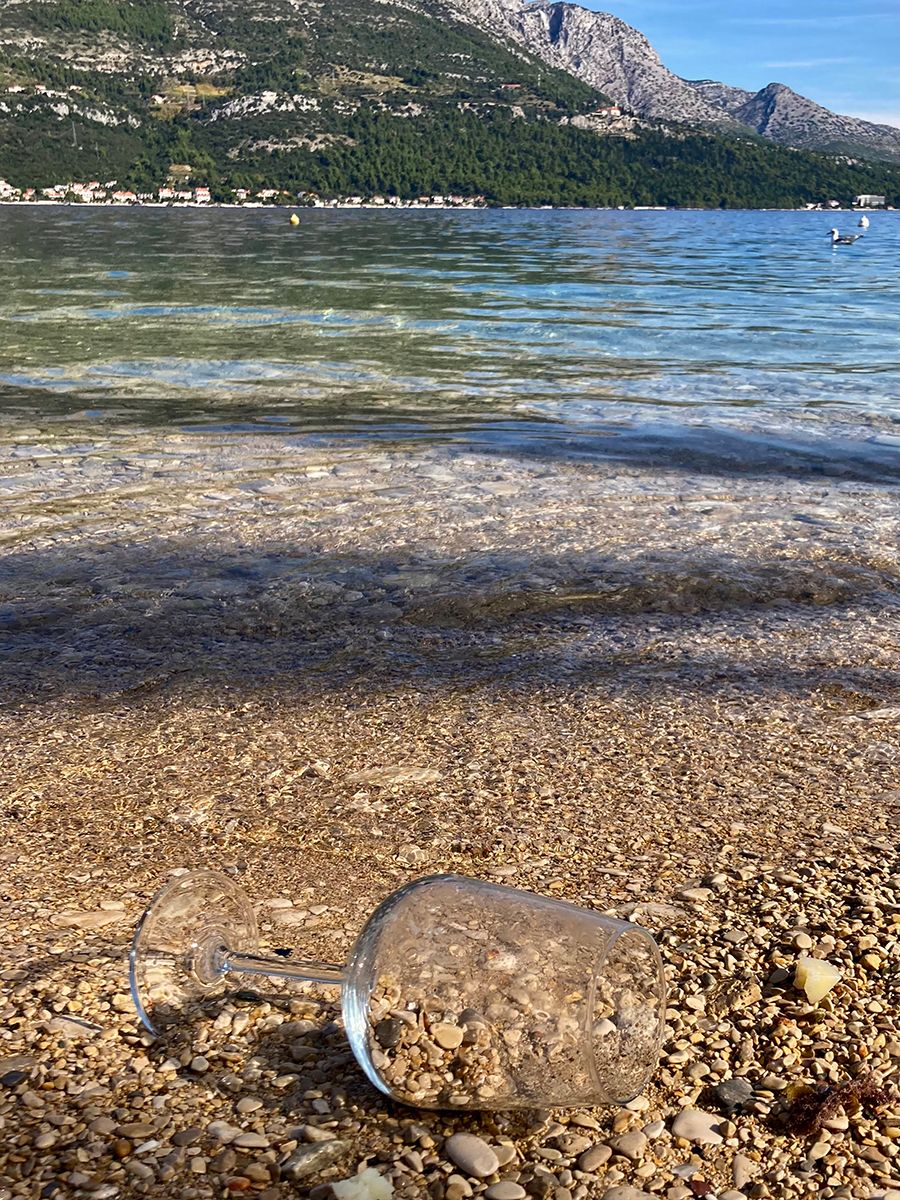

Then, she returned to her pier. She was absolutely happy. This time, it took her a bit longer than 22 days to feel better—25 or so—but she did eventually. She was sitting there, watching glares on the water through the pier planks, thinking that maybe not everything is being destroyed, or not completely, or not irrevocably, or not yet. Something is being taken, something else is given. She remembered how right upon her arrival the night wind broke a wine glass she left at the rooftop veranda, and the very next morning she found an identical, even nicer one, at the beach in front of the Dominican Monastery of the Guardian Angel, filled with sand and seashells. The immediate compensation, a welcoming gift from the sea—impressive client service.

She was thinking of how well she knew herself and how cunningly she tricked herself, again, into an adventure, into a ploy that required coming out of self-isolation, into a narrative with a driving force and a structure emerging from overwhelming chaos. Symbolic gestures still work—these two planks were like the past two years of her life—dark, dropped out, a hole; alien, taken from another place—yet now they are a patch, a bridge, a berth, parts of the whole.

It was November 4, the full moon eve. A tremendous pearl plate was rising from behind the hills of the neighboring peninsula in broad daylight, while the sun was still rolling to the Western side of the island—she could see both, it was spectacular, and she had 10 more days to enjoy life.

For about 20 minutes she was experiencing catharsis, the gestalt closure, satisfaction, you name it. But 20 minutes later, her phone would mysteriously slip into the sea, she would be forced to dive for it, would get a graze on her buttock, lose access to tons of important (unsynced) data and bank cards, wouldn’t take a single photo— in short, enjoying life would become tricky again—but all that wouldn’t be of the matter.

She would dry off, her scars would heal—some, the data would be restored; she would write another short story, would come up with the idea of a film—even shoot and watch it in her head; would keep greeting her neighbours, constructors, the last bartender, her beach mate—a grey-haired gentleman with A-4 sheets he made notes on, and yet another would start saying to her daily ‘Bok! Plivala?”—almost like aunty Antica did. Something is taken by the sea, something else is given in return, right?

A few days after the incident, when the old town was filled with a choir of saws, she decided— for the first time ever—to count the planks of her pier to discover that they were, and have always been, twenty two.

“For real? Are you kidding me?” She recounted them, but they were 22 dead serious planks. Then she counted screws she nailed—let’s be obsessive-compulsive till the end, she said to sea urchins—there were twenty or twenty-one. Imperfect.

She returned to the crime scene—the veranda she stole her repair kit from, and hardly found three used screws in the ground. Came back, nailed two of them—“Screw the numbers”—but the last one, bent, got stuck, so she was forced to extract it. It left a hole in the white wood that bugged her inner perfectionist, but just slightly. It wasn’t that piercing feeling of open-endedness her previous short story had—just a tiny imperfection and a task for the next year. Although even that story she managed to give a nice finale this year.

A day before departure she went for a swim. The water was cold—almost mid-November—getting into it took some guts. She was alone at the beach and decided to use—for a change—the ladder into the sea that a grey-haired gentleman usually uses. She stepped into the transparent and calm, like mirrored glass, water—right at her feet, on a large, square-as-a-box stone lay a big, perfect silver-shining screw. A farewell gift from the sea.

“Okay, you nailed it”, she laughed and went for a hammer.

And now there were 22 planks, 24 nails and zero holes. Completeness it is.

Where Morning Begins

Sun Kissed Flowers

I listen to the bread

Shut Up and Shoot

A short note before Friday

Bambusikha

Cardamon Spell — one day only

The Road to the Meadow of Awakening

Giraffe Tapes returns home

About us

GiraffeHome — a place where food remembers why it was created

The Shadow That Knew the Light

The Fog That Remembers

The Alchemy of the Sea Buckthorn

Fado of the Dying Sun

Peter’s Pigeons

Whispers of the Acacia

Miro and the Three Days

Lift your gaze

Igo and the Silence He Heard

Lucia and the Voice That Woke Up Late

The Kitchen Where the World Comes Alive

I, Tejo, Architect of Unspoken Worlds

The Summit That Breathes Light

Where the Crickets Sing

To my grandmother Annushka

Odysseus

Victor’s plant

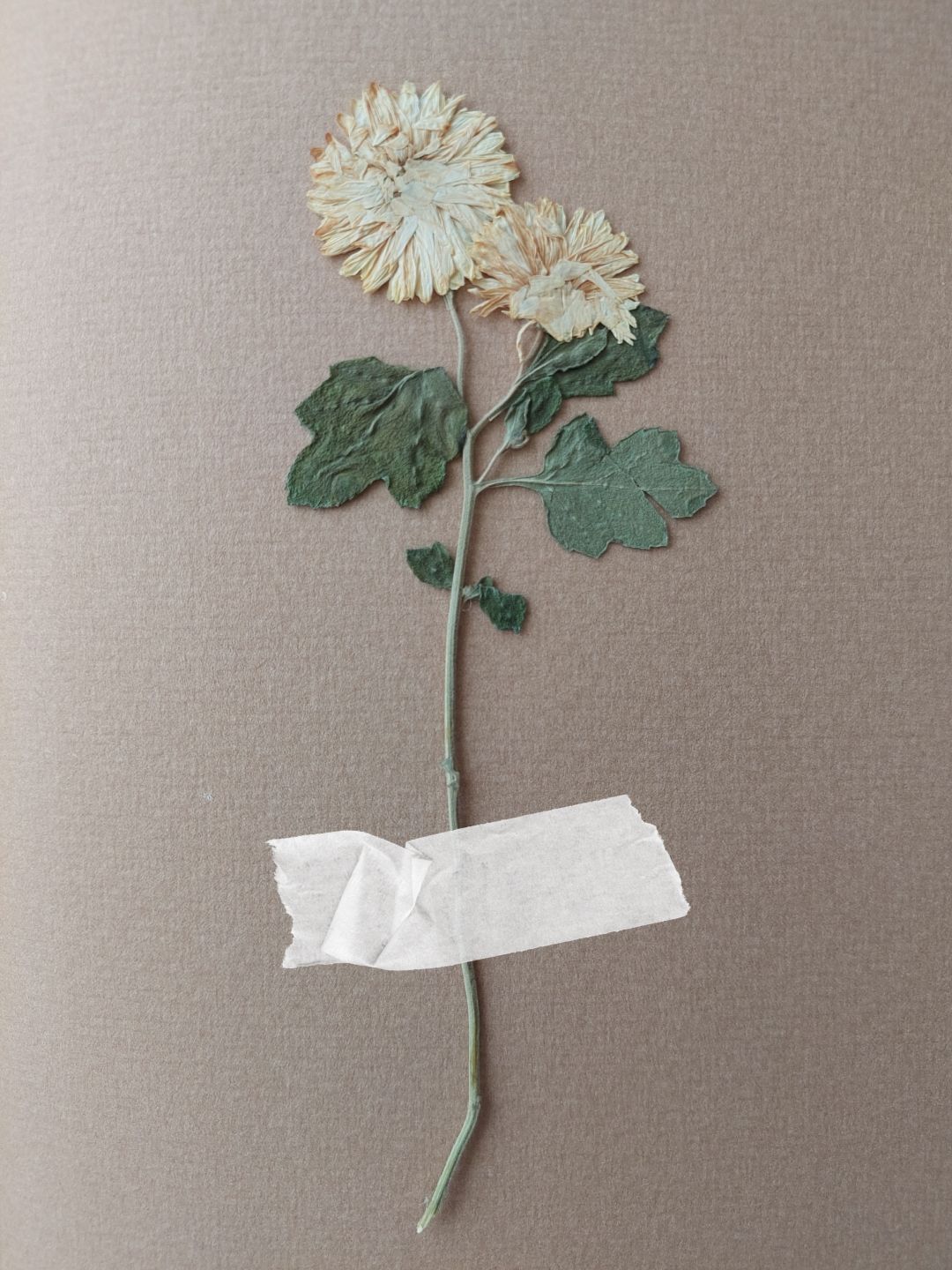

Lila’s Herbarium

When the Birds Return

Where Sound Ends: Ambient as a Way of Being

Not by path, but by memory

The bread rose in the oven

New Merch from giraffehome — Artifacts of Time on T-Shirts. Coming Soon

The Light Within

When the trees were small

Light through the window

I am giraffe tapes

The ocean

Analog vibes only

Priceless

A Lonely Tree Between Worlds

The Juggler from Childhood

The story of a certain rabbit

One Shot, One Chance

Reflection is looking at you

And we pretend to understand

A space of inspiration

Love people not labels

Grandmother’s Rushnyks

Stay analog

Indian memories and captured radio waves via Rusted Tone Recordings

Film is not dead

Letters that were never sent

Sometimes a period is just a comma

The old wallpaper

Press play. Stay analog.

Play. Pause. Repeat.

What does the brick hide?

History speaks

Photography isn’t just an image

The funicular glides slowly

Black and white symphony